The Third Pole

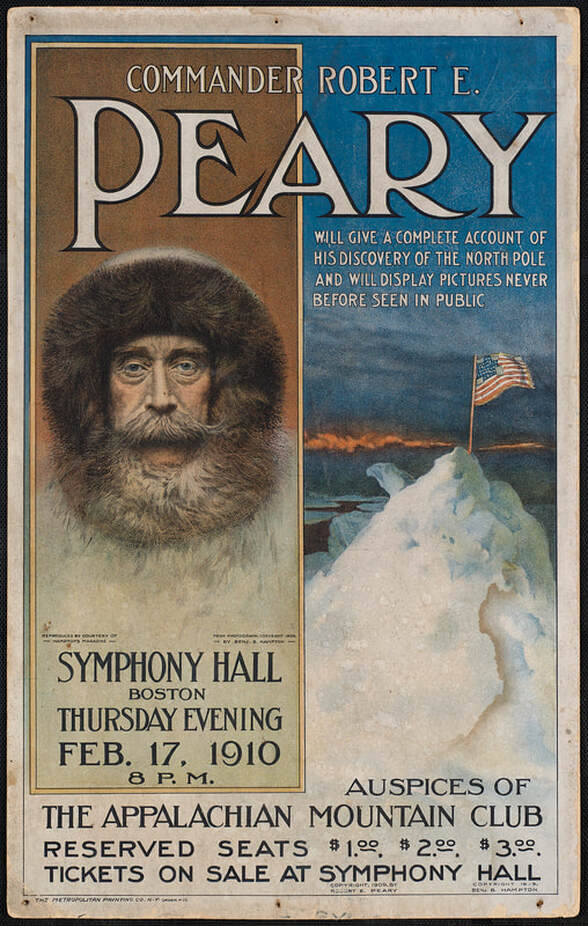

The decades before the First World War were the so-called ‘Heroic Age of Polar Exploration’,

a time when expeditions, after many failures, finally succeeded in reaching the North and South Poles.

Those successes had been American and Norwegian, causing British explorers to seek out new opportunities.

So, the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club resolved to send a British-funded expedition to Mount Everest.

Their reconnaissance team would map Earth’s highest peak - it's ‘Third Pole’ - in preparation for later attempts to reach the summit.

a time when expeditions, after many failures, finally succeeded in reaching the North and South Poles.

Those successes had been American and Norwegian, causing British explorers to seek out new opportunities.

So, the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club resolved to send a British-funded expedition to Mount Everest.

Their reconnaissance team would map Earth’s highest peak - it's ‘Third Pole’ - in preparation for later attempts to reach the summit.

Author and mountaineer Frank Nugent discusses

global exploration in the early 20th Century

global exploration in the early 20th Century

|

Preparing the way: 1919-1921

Since the 1890s, British organisations such as the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) and the Alpine Club, had explored the possibility of sending an expedition to Mount Everest. Among the most vocal advocates of such an expedition were British army officers stationed in India such as Sir Francis Younghusband and Charles Bruce (later a brigadier-general). Bruce and Younghusband sought permission to mount an Everest expedition in the early 1900s, but they were unable to obtain the necessary political and diplomatic backing. Another advocate was British army officer John Noel, who secretly entered Tibet in 1913. He eventually got within 65 kilometres of Mount Everest, a journey that later received much public attention. Noel's travels and the efforts of Bruce and Younghusband meant that the idea of an Everest expedition remained alive and, early in 1919, Charles Howard-Bury wrote to the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) suggesting that a reconnaissance of Mount Everest should be made as soon as possible, to be followed by an attempt to reach the summit. Although the RGS was keen to act upon Howard-Bury's proposal, it was rejected by the Indian Office. Nevertheless, Howard-Bury, with the backing of the RGS, visited India in 1920 and crossed the border into Tibet. There he met with Charles Bell, who managed relations with Tibet on behalf of the British administration in India and who was held in high regard by Tibetan officials.

Towards the end of 1920, Bell travelled to the Dalai Lama's private estate on the outskirts of the Tibetan capital, Lhasa. Subsequently, the Dalai Lama granted permission for an expedition to trek through southern Tibet in order to reach and map Mount Everest. News of the Dalai Lama's decision spurred the RGS and the Alpine Club into action. They formed the Everest Committee with Sir Francis Younghusband (RGS president since 1919) as chairperson and John Norman Collie (Alpine Club president since 1920) as a committee member. The committee resolved that the main goal for 1921 should be reconnaissance: 'This does not debar the mountain party from climbing as high as possible on a favourable route but attempts on a particular route must not be prolonged to hinder the completion of the reconnaissance.' The committee appointed Charles Howard-Bury as expedition leader. Initially, the role was expected to be given to Charles Bruce, who was renowned for his explorations in the Himalayas, but he had recently taken up a new appointment and was unavailable. Nevertheless, the committee were happy to award the role to Howard-Bury. It was largely through his efforts that the expedition had received permission to enter Tibet and he had previously travelled along the outskirts of the country. Howard-Bury had experience of military command and his Tian Shan journey demonstrated his ability to successfully navigate through unfamiliar terrain and cultures. Also, he was willing to pay his own travel and equipment expenses: a significant gesture given that the Everest Committee was unable to fund the expedition from its own resources. It relied upon contributions from members of the RGS and the Alpine Club as well as photographic rights deals with London's The Times, the Philadelphia Ledger and the Graphic, an English illustrated weekly paper. |

|

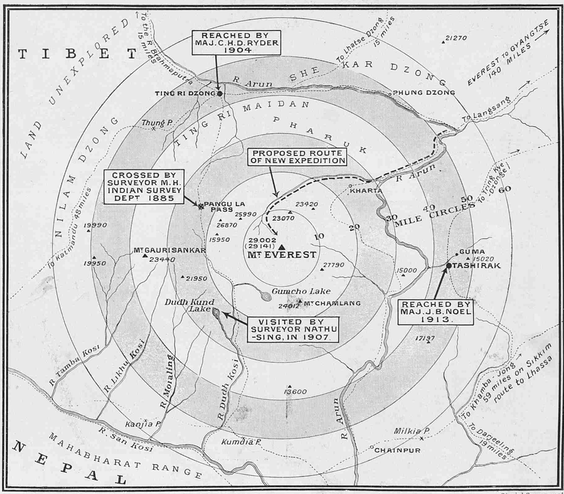

Before 1921, very little was known about Mount Everest, apart from its place as the world's highest mountain. As the above map shows, no expedition had reached the mountain at that time. The 1921 Reconnaissance Team would travel via Tingri Dzong and establish a base camp at Kharta. Taken from The Sphere, an illustrated weekly newspaper, 5 February 1921.

|

Frank Nugent explains how Charles Howard-Bury was instrumental to the Alpine Club and the Royal Geographic Society in organising the 1921 expedition

To The Jongpens and Headmen of Pharijong, Ting-ke, Khamba and Kharta.

You are to bear in mind that a party of Sahibs are coming to see the Chha-mo-lung-ma mountain and they will evince great friendship towards the Tibetans. On the request of the Great Minister Bell a passport has been issued requiring you and all officials and subjects of the Tibetan Government to supply transport, e.g. riding ponies, pack animals and coolies as required by the Sahibs, the rates for which should be fixed to mutual satisfaction. Any other assistance that the Sahibs may require either by day or by night, on the march or during halts, should be faithfully given, and their requirements about transport or anything else should be promptly attended to. All the people of the country, wherever the Sahibs may happen to come, should render all necessary assistance in the best possible way, in order to maintain friendly relations between the British and Tibetan Governments.

Dispatched during the Iron-Bird Year.

Seal of the Prime Minister.

A Translation of the passport given to the reconnaissance expedition 'by the Government at Lhasa under the seal of the Prime Minister of Tibet'. In 1920, British diplomat Charles Bell sought approval from the Tibetan government for an expedition to Tibet. His pleas were granted, allowing the reconnaissance expedition to take place in the following year. The translation is taken from the official account of the 1921 expedition.

A view of Makalu and Chomolönzo, about 20 kilometres south-east of Everest, taken during the 1921 reconnaissance. In his account of the expedition, Howard-Bury described viewing those peaks one morning in August 1921: 'As soon as I had finished breakfast I climbed up 1,000 feet behind the camp; opposite me were the wonderful white cliffs of Chomolönzo and Makalu, which dropped almost sheer for 11,000 feet into the valley below. Close at hand were precipices of black rock on which, in the dark hollows, nestled a few dirty glaciers.' (Marian Keaney/Westmeath Library Services: Howard-Bury Collection)