Taking the First Steps

Charles Howard-Bury led an experienced team, most of whom had previously

climbed in the Alps and the Himalayas. Yet they encountered many difficulties during their

trek from Darjeeling through Sikkim and across southern Tibet, with sickness and high altitude taking a toll.

climbed in the Alps and the Himalayas. Yet they encountered many difficulties during their

trek from Darjeeling through Sikkim and across southern Tibet, with sickness and high altitude taking a toll.

The reconnaissance team was given specific goals, as described by Frank Nugent

|

From Darjeeling into Tibet: May, June 1921

|

|

The reconnaissance expedition departed from Darjeeling in May 1921. Henry Morshead, who led the expedition's survey party, set out first along with his surveyors and baggage-carriers. The main party, led by Howard-Bury, followed soon after. It was broken into two groups, travelling one day apart.

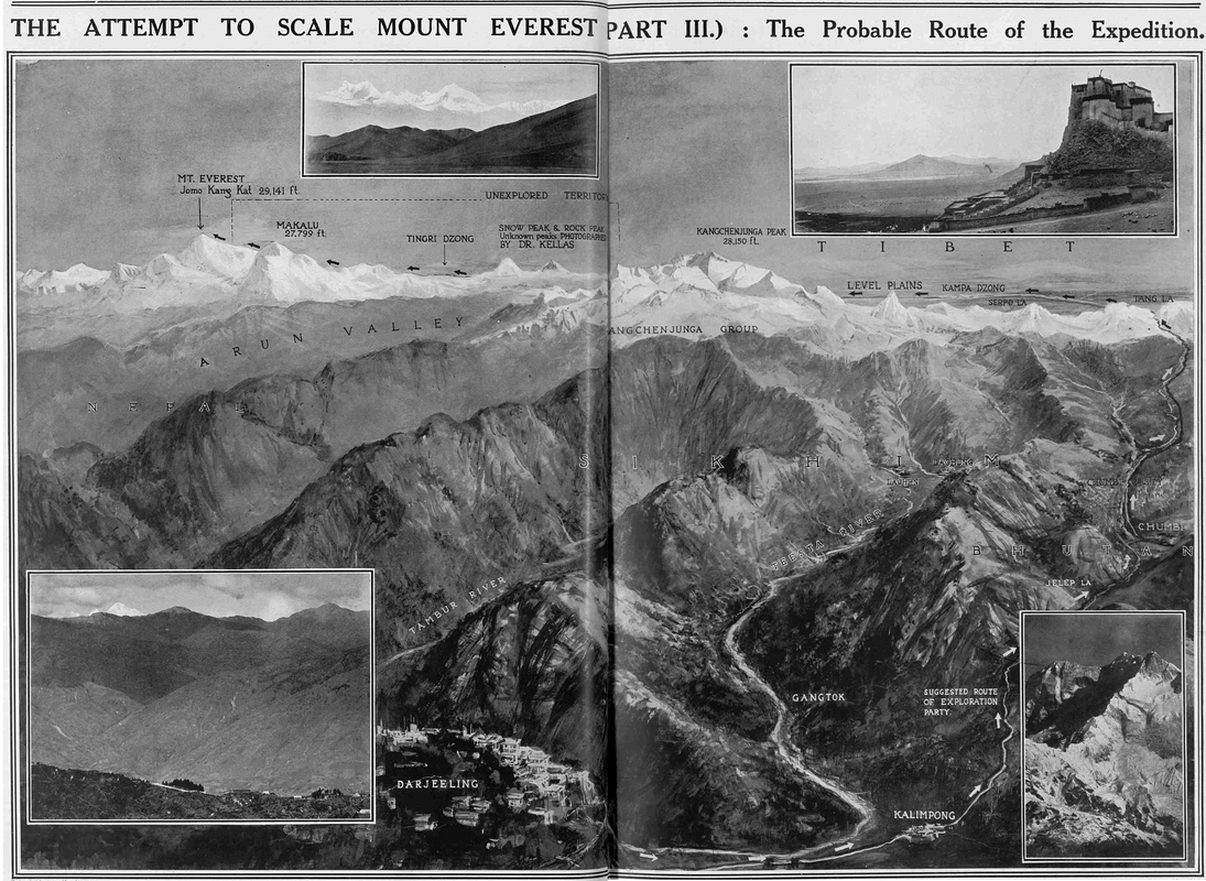

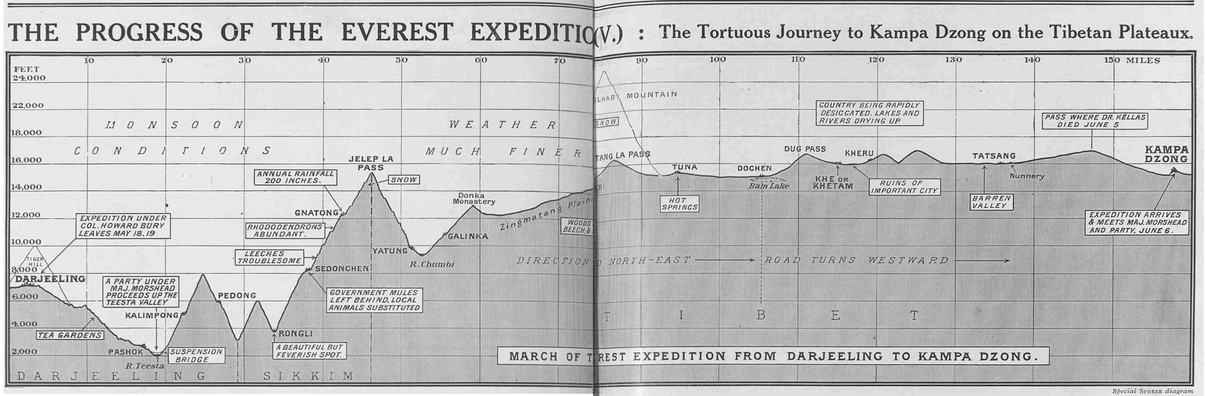

The expedition's equipment and belongings were carried by 100 mules supplied by the British army. These animals proved inadequate to the task, being, as described by Howard-Bury, 'fat from the plains where they had had very little work to do'. During the following few weeks, much of Howard-Bury's time was devoted to finding replacements and, at each village, he hired local mules, gradually improving the quality of the animals in the baggage train. After leaving Darjeeling (as can be seen in the map below), the expedition passed through heavily forested countryside in the direction of the Jelep La (a mountain pass at an elevation of over 4,700 metres). As it approached the Jelep La, the expedition was met by 'a plague of leeches', so numerous that they, according to Howard-Bury, 'sat upon every stone waving at the passer-by'. Fortunately, the expedition was able to move quickly trough the 'zone of leeches' and into an area of towering rhododendrons as it ascended towards the Jelep La. Once through the gap, the expedition had entered Tibet. It then descended into the Chumbi Valley and headed north towards towards the Tang La (at about 4,600 metres), which Howard-Bury described as 'a very gentle and scarcely perceptible pass'. After the Tang La, the expedition continued north along a route that would eventually have brought it to Lhasa, the Tibetan capital. However, the expedition soon branched off that road, turning west in the direction of Mount Everest. After a few days of, to use Howard Bury's words, an 'easy march' his group reached Kheru, encountering: 'some people belonging to a nomad tribe who always lived in tents. They were very friendly, put tents at our disposal, and did their best to make us comfortable.' A few days later, Howard-Bury's group reached Khamba Dzong (the fort at khamba - the name is also spelt as Kampa, Kamba and Gamba) in Tibet, the location at which the expedition was due to reassemble. Morsehead's party of surveyors had arrived there nine days earlier. However, some members of the expedition were, as we shall see blow, struggling to make progress. |

A map that appeared in The Sphere, an illustrated weekly newspaper published in England. It is from the edition of 9 April 1921. Even before the reconnaissance mission began in May 1921, it had already captured the attention of the press. Over the following months, newspapers carried regular reports about the expedition, often printing dispatches written by Howard-Bury.

|

You can download the map

through this link |

| ||||||

The 1921 Reconnaissance Team

Standing from Left to right are: Guy Bullock, Henry Morshead, Oliver Wheeler and George Leigh Mallory. Seated from left to right are: Alexander Heron, Alexander Wollaston, Charles Howard-Bury and Harold Raeburn. This colourised image was part of a collection of slides and negatives given to the Royal Geographical Society by Sandra Noel, daughter of the British mountaineer and filmmaker John Noel. It seems likely that he carried out the colour work on this image. The image is reproduced with permission of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG). A b/w version of the photo is available in Mullingar Public Library.

|

Pictured Charles Howard-Bury (1883-1963) was the leader of the 1921 reconnaissance expedition. Guy H. Bullock (1887-1956). Along with George Leigh Mallory, he was the expedition's main climber. Bullock had much experience of climbing in the Alps alongside Mallory. Henry T. Morshead (1882-1931) led the 1921 expedition's survey party. Morshead joined the Survey of India in 1906, having previously been a surveyor with the Indian Army and the Royal Engineers. An experienced mountaineer, he would later join the 1922 and 1924 expeditions to Mount Everest. E. Oliver Wheeler (1890-1962) was the key figure in the 1921 expedition's attempts to map Everest, conducting the first photo-surveys of the mountain and surrounding region. He became surveyor-general of India in 1941. George Leigh Mallory (1886-1924) was one of the expedition's climbing team. Mallory was a very experienced Alpine climber and he would also participate in the 1922 and 1924 British expeditions to Everest. He died, along with fellow climber Andrew Irvine, in their attempt to reach the summit of Mount Everest during the 1924 expedition. Alexander M. Heron (1884-1971). A Scottish geologist, who worked with the Geological Survey of India. His geological map of the Everest region was included in the official account of the expedition. Alexander F.R. Wollaston (1875-1930). A surgeon, he was the expedition's doctor and naturalist. Wollaston had previously made expeditions to Uganda and New Guinea. Harold A. Raeburn (1865-1926) was a Scottish ornithologist. An experienced mountaineer, who had climbed in the Alps, the Caucasus and, during 1920, in the Himalayas. A member of the climbing team, his contribution to the expedition would be limited by illness. Not Pictured

(Not Pictured) Alexander M. Kellas (1868-1921) was a Scottish chemist, who participated in eight Himalayan climbing expeditions between 1907 and 1921. He conducted experiments to assess the use of oxygen at high altitudes and is credited with recognizing the importance of including Sherpas in high-altitude expeditions.

(Not Pictured) Surveyors Lalbir Singh Thapa, Gujjar Singh, Turubaz Khan and photographer Abdul Jalil Khan. A photo of the surveyors at work is provided later in the exhibition. Gyalzen Kazi and Chhetan Wangdi (their photo is provided later) acted as interpreters and guides. The group had a Tibetan cook named Poo. Howard-Bury said of him: he 'accompanied me in all my wanderings, and I could not have found a more useful servant when travelling, as he never seemed to mind the cold or the height and could always produce a fire of some kind...' |

An epic Landscape. A member of the reconnaissance team can be seen standing by the river. (Marian Keaney/Westmeath Library Services: Howard-Bury Collection)

|

Frank Nugent describes the clothing worn by the reconnaissance team as protection against the harsh climate at high altitudes.

Wool was their favoured material and Guy Bullock described one climb in the vicinity of Everest: 'The wind was strong and cold, but did not go through my clothes at once. I was wearing three pairs of drawers and three Shetland sweaters.'

Wool was their favoured material and Guy Bullock described one climb in the vicinity of Everest: 'The wind was strong and cold, but did not go through my clothes at once. I was wearing three pairs of drawers and three Shetland sweaters.'

The death of Kellas: June 1921

|

Shortly after entering Tibet, Alexander Kellas became seriously ill and had to be carried on a litter during subsequent days. At times, Kellas appeared to be recovering but each sign of hope was followed by a relapse. It seems that the reconnaissance team, and perhaps Kellas himself, did not realise the seriousness of his condition. Howard-Bury later described hearing news that Kellas had died: 'While we were talking, a man came running up to us very excitedly to say that Dr. Kellas had suddenly died on the way. We could hardly believe this, as he was apparently gradually getting better; but Wollaston at once rode off to see if it was true, and unfortunately found that there was no doubt about it. It was a case of sudden failure of the heart, due to his weak condition, while being carried over the high pass.'

The following day the team buried him 'on the slopes of the hill to the South of Khamba Dzong, in a site unsurpassed for beauty that looks across the broad plains of Tibet to the mighty chain of the Himalayas out of which rise up the three great peaks of Pawhunri, Kanchenjhow and Chomiomo, which he alone had climbed.' From the same spot, almost 200 kilometres away, could be seen the white crest of Mount Everest. The exhibition had lost its most experienced Himalayan climber and Harold Raeburn's condition was also worrisome. He was suffering from stomach pains and had fallen from his pony on at least two occasions. A few days later, Howard-Bury sent Raeburn back to Sikkim, where he would recuperate. Although Raeburn subsequently rejoined the expedition, he played little part in subsequent events. The climbing team was now reduced to two: George Mallory and Guy Bullock. Much would depend on whether they could overcome unfamiliar challenges in unforgiving terrain. |

A diagram that appeared in the Sphere, 6 August 1921, showing the reconnaissance team's expedition route as far as Khamba Dzong, a hillside fortress.

The paper provided measurements in feet: 16,000 feet corresponds to almost 4,900 metres.

The paper provided measurements in feet: 16,000 feet corresponds to almost 4,900 metres.

A small monument marks the grave of Alexander Kellas, as shown in a photo taken during the 1922 expedition to Everest (Alpine Club Photo Library, London)

Howard-Bury later recounted the day in which the team placed a marker over Kellas's grave during their return journey at the end of the expedition:

'All day to the South there was a furious storm raging along the Himalayas, and when it cleared up in the evening there had evidently been a heavy snowfall.

In the course of the afternoon we put up over Dr. Kellas's grave the stone which the Jongpen had had engraved for us during our absence.

On it were inscribed in English and Tibetan characters his initials and the date of his death, and this marks his last resting-place.'

Howard-Bury later recounted the day in which the team placed a marker over Kellas's grave during their return journey at the end of the expedition:

'All day to the South there was a furious storm raging along the Himalayas, and when it cleared up in the evening there had evidently been a heavy snowfall.

In the course of the afternoon we put up over Dr. Kellas's grave the stone which the Jongpen had had engraved for us during our absence.

On it were inscribed in English and Tibetan characters his initials and the date of his death, and this marks his last resting-place.'

It may seem an irony of fate that actually on the day after the distressing event of Dr. Kellas' death we experienced the strange elation of seeing Everest for the first time. It was a perfect early morning as we plodded up the barren slopes above our camp and rising behind the old rugged fort which is itself a singularly impressive and dramatic spectacle; we had mounted perhaps a thousand feet when we stayed and turned, and saw what we came to see. There was no mistaking the two great peaks in the West: that to the left must be Makalu, grey, severe and yet distinctly graceful, and the other away to the right—who could doubt its identity? It was a prodigious white fang excrescent from the jaw of the world. We saw Mount Everest not quite sharply defined on account of a slight haze in that direction; this circumstance added a touch of mystery and grandeur; we were satisfied that the highest of mountains would not disappoint us.

George Leigh Mallory describes the team's first view of Mount Everest in the distance