Tibet in 1921

Howard-Bury was an explorer more than he was a mountaineer.

As the expedition travelled through Tibet, he took time to learn about the country and

to photograph its people. Tibet was then an independent country, after expelling Chinese forces in 1912,

and the reconnaissance team relied upon the official support of the Tibetan state and the assistance of individual Tibetans.

As the expedition travelled through Tibet, he took time to learn about the country and

to photograph its people. Tibet was then an independent country, after expelling Chinese forces in 1912,

and the reconnaissance team relied upon the official support of the Tibetan state and the assistance of individual Tibetans.

|

The reconnaissance expedition travelled through an independent Tibet but that independence was fragile and forever threatened by the machinations of the great powers. The first two decades of the 20th century saw Tibet at the centre of the geopolitical struggle in which the British and Chinese were the leading actors, with Russia, Japan and others watching from the wings.

Britain attacks Tibet

Thubten Gyatso, the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, later nicknamed 'the Great Thirteen', was enthroned at the age of three in 1879 and remained until his death in 1933 the temporal and spiritual leader of Tibet. (The current Dalai Lama is the fourteenth.) By 1920, when he gave permission for the Everest reconnaissance to enter Tibet, the Dalai Lama had been forced to flee his country on two occasions; once to escape British forces, on another to escape the Chinese army.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, elements of the British administration in India feared that tsarist Russia was seeking to influence or undermine the British Empire's largest and most valuable colony. At that time, Britain’s Governor-General, or Viceroy, was George Nathaniel Curzon, the 1st Marquess of Kedleston. Curzon became increasingly perturbed by reports that Russia was extending its influence in Tibet. He feared that Tibet could become a Russian protectorate, although his military advisers believed the Russian threat to India to be vastly overblown. Nevertheless, Curzon decided to send a military force into Tibet. The invasion was intended to force the Tibetan government to act in a manner that meshed with British interests and to keep Tibet, whether it was an independent state or a province of China, as a neutral or pro-British buffer separating tsarist Russia from India. The invasion was led by Francis Younghusband, who would go on to chair the Mount Everest Committee that oversaw and sponsored Howard-Bury's reconnaissance mission in 1921. Younghusband led a force from Sikkim across the Jelap Pass into Tibet on 12 December 1903. His destination was Lhasa and he brought with him more than 1,000 soldiers, two Maxim machine guns, four artillery pieces, 10,000 laborers, 7,000 mules, 4,000 yaks and six camels. This was a force that the Tibetans were unable to withstand, given that that their army consisted mostly of monks and poorly armed farmers who had been pressed into military service. Outside the village of Guru, the invaders encountered an encampment of 1,500 Tibetan troops. The British force, which included Sikhs and Gurkhas, opened fire, killing an estimated 700 Tibetans. They had further 'victories' over Tibetan forces during subsequent weeks, bringing the total Tibetan death toll to over 1,000. The British force arrived in Lhasa to discover that the Dalai Lama had fled to Mongolia. They found no evidence of any treaty between the Dalai Lama and the Russian Tsar, although that did not prevent Younghusband from compelling the Tibetans to sign an Anglo-Tibetan Convention, which set out a number of commercial and political provisions that were advantageous to the British Empire. The convention also forced a Tibet to pay a massive and unaffordable war indemnity. The terms of the treaty, forced upon the Tibetans at gunpoint, were condemned internationally while Younghusband's actions were criticised in London. The indemnity was subsequently reduced by the British government, who signed an accord with China in 1906. In return for payment, the British agreed not to annex or interfere in Tibet, while China engaged not to permit any other other state to interfere with the territory or internal administration of Tibet. China invades and retreats

In 1910, China sent military forces to Tibet, establishing control over most of the country and forcing the Dalai Lama to flee to India. Chinese control was short-lived. During 1911 and 1912, China's Qing dynasty was toppled, leading to the creation of a Chinese republic. Tibetans took advantage of the chaos within China and rose up against Chinese troops based in Lhasa. By the end of 1912, most Chinese forces had departed Tibet and the Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa in January 1913. Tibet was now a de facto independent country, a status it retained until the Chinese invasion of 1950.

After returning to Tibet, the Dalai Lama faced the long-term problem of maintaining the country's borders and independence, with the British Empire to its south and the Republic of China to its north and east. That situation required Tibet to maintain relations with its neighbours, while keeping tight control over who could, and could not, enter its territory. It was in this context that the Howard-Bury and Charles Bell carried out their successful diplomatic work in 1920. By that stage, Britain had agreed, through its treaty with China in 1906 and a subsequent treaty in 1914 (signed by Britain and Tibet but not by China), that it would not enter Tibetan territory. Britain was also negotiating to supply arms to Tibet, which was trying to modernise its army. Allowing the reconnaissance mission to travel through Tibet was a relatively risk-free means by which the Tibetan state could enhance its relationship with Britain and vice versa (British officials spent much of 1921 in negotiations with the Tibetan government). Howard-Bury was aware of those overlapping goals and was eager to present Tibetans with a favourable view of the British Empire. In Mount Everest: the Reconnaissance he acknowledged that: 'In these out-of-the-way parts they had heard vaguely of the fighting in 1904, and they imagined that our visit might be on the same lines... They were therefore much surprised when they found that we treated them fairly and paid for everything that we wanted at very good rates. The Expedition may, I venture to think, take credit to itself for having certainly done a great deal of good in promoting more friendly relations between the Tibetans and ourselves...' |

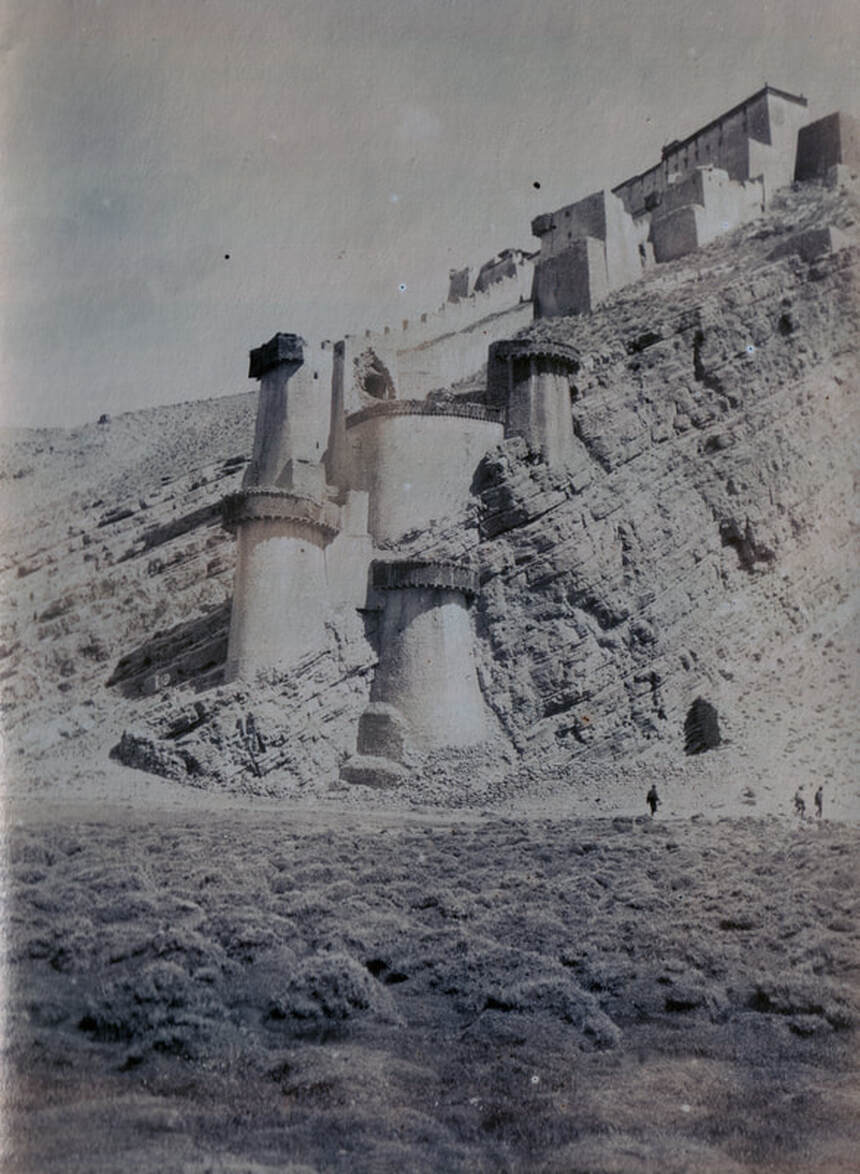

The fort (or Dzong) at Khamba (the name is also spelt as Kampa, Kamba and Gamba). Khamba is a Tibetan village north of Sikkim. Howard-Bury described his time at the fort in 1921: 'Our camp at Khamba Dzong was pitched in a walled enclosure at the foot of the fort, built on a great crag that rose 500 feet sheer above us. They called this enclosure a Bagichah, or garden, because it once boasted of three willow trees. Only one of these three is alive to-day, the other two being merely dead stumps of wood. The Jongpen [governor] here, who was under the direct orders of Shigatse [a city in southern Tibet which is home to the Panchen Lama, one of the most important figures in Tibetan Buddhism], was very friendly, and after our arrival presented us with five live sheep, a hundred eggs, and a small carpet which he had made in his own factory in the fort.' (Marian Keaney/Westmeath Library Services: Howard-Bury Collection)

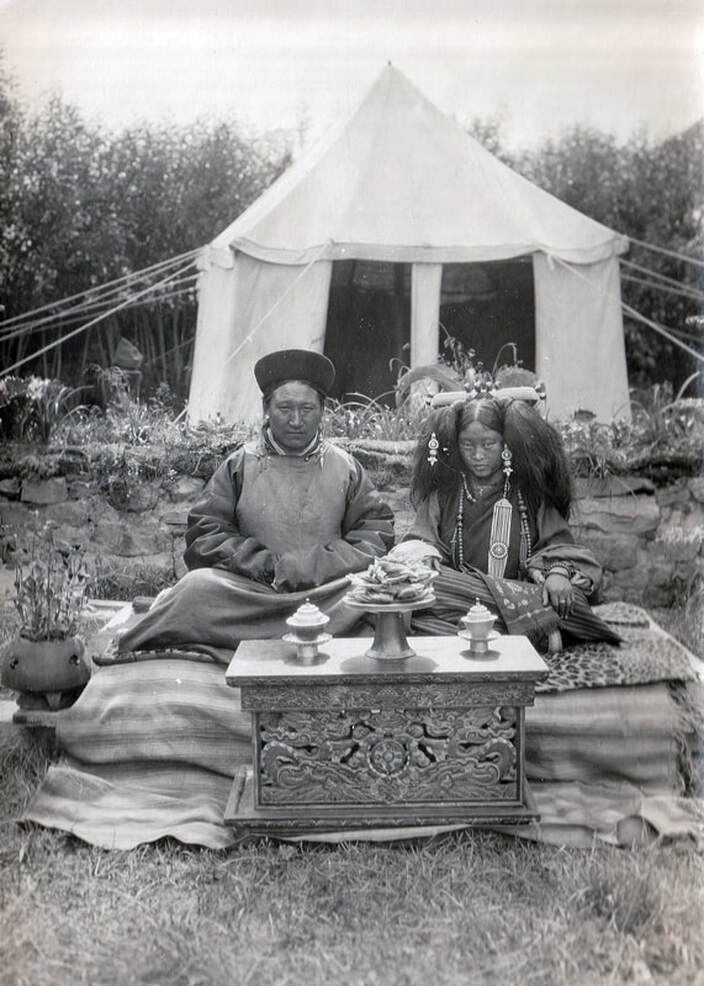

The 'Dzongpen of Kharta and his Wife', photographed by Howard-Bury. He later described the scene: '...with Bullock, I went to pay an official visit to the Jongpen [governor - both Dzongpen and Jongpen are used in the official narrative] at Kharta Shiga. He had made great preparations to receive us, and had put up a large tent in which Chinese carpets and tables were set out with pots of flowers arranged all round. Soon after our arrival we were given a most copious meal: bowl after bowl of well cooked macaroni and mince with pickled radishes and chillies were set before us. After we had finished this meal, I induced the Jongpen and his young wife to be photographed. She had a most elaborate head-dress of coral and pearls, with masses of false hair on either side of her head.' (Marian Keaney/Westmeath Library Services: Howard-Bury Collection)

The Depon [commander/governor] of Tingri Region, his Wife and her Mother. Howard-Bury later described the circumstances behind this photo: 'The Depon here, who was acting as the Governor of the place, was a nice young fellow and very cheery, and later on I got to know him very well and went over to his house and was entertained by him and his wife. He told me that the Tibetans still paid tribute to Nepal for all that part of the country, and that the amount they had to pay was the equivalent of 5,000 rupees per annum. The Nepalese kept a head-man at Tingri and another at Nyenyam to deal with all criminal cases and offences committed by Nepalese subjects when in Tibet. I found later on that the Tibetans were very frightened of the Nepalese, or of having any dealings with a Gurkha. I took photographs of the Depon's wife and all their children, and of his mother-in-law, which delighted them immensely; the wife at first was very shy of coming forward, but after many tears and protestations her husband finally induced her to be photographed... The officials, as a rule, have a long ear-ring, 4 or 5 inches long, of turquoises and pearls, suspended from the left ear, while in the right ear they wear a single turquoise of very good quality. Nearly every one carries a rosary, with which their hands are playing about the whole day.' (Marian Keaney/Westmeath Library Services: Howard-Bury Collection)

Howard-Bury took this photo of the Depon's wife and children: 'The great semi-circular head-dresses that the women wear are usually covered with turquoises, and coral, and often with strings of seed pearls across them. Round their necks hang long chains of either turquoise or coral beads, sometimes mixed with lumps of amber. Suspended round the neck by a shorter chain is generally a very elaborately decorated charm box, those belonging to the richer or upper classes being of gold inlaid with turquoises, the poorer people having them made of silver with poorer turquoises ... We were told that the laws governing marriage in those parts were strictly regulated. Owing to the excessive number of males, a form of polyandry prevails. If there were four brothers in a family, and the eldest one married a wife, his wife would also be the property of the three younger brothers; but if the second or third brother married, their wives would be common only to themselves and their youngest brother.' (Marian Keaney/Westmeath Library Services: Howard-Bury Collection)

'Sergeants and Retainers' in the employment of the Depon of Tingri. These are probably members of the 'military garrison' mentioned by Howard-Bury. It was comprised, he wrote, 'only of a sergeant and four or five soldiers'. (Marian Keaney/Westmeath Library Services: Howard-Bury Collection)

Hot springs in Tibet (perhaps those at a place called Tsamda). Howard-Bury made numerous reference to hot springs in the official account of the expedition. He described visiting one spring: 'On July 17 I made an excursion out to the Hot Springs at Tsamda, about 7 miles away to the North-west across the plain. The valley of the Bhong-chu narrows there for a few miles before opening out again into the wide Sutso Plain. There were two or three hot springs here, but only one large one, and this was enclosed by walls within which were little stone huts in which people could change their clothes. The water was just the right temperature for a nice hot bath.' He also visited the hot springs at Kambu: 'There is a curious account of these springs written by an old Lama... The writer describes the Upper Kambu Valley as quite a pleasant spot where cooling streams and medicinal plants are found in abundance. Medicinal waters of five kinds flow from the rocks, forming twelve pools, the waters of which are efficacious in curing the 440 diseases to which the human race is subject.' (Marian Keaney/Westmeath Library Services: Howard-Bury Collection)

A group of young Tibetans (Marian Keaney/Westmeath Library Services: Howard-Bury Collection)

Abbott seated at Khamba Dzong (Marian Keaney/Westmeath Library Services: Howard-Bury Collection)

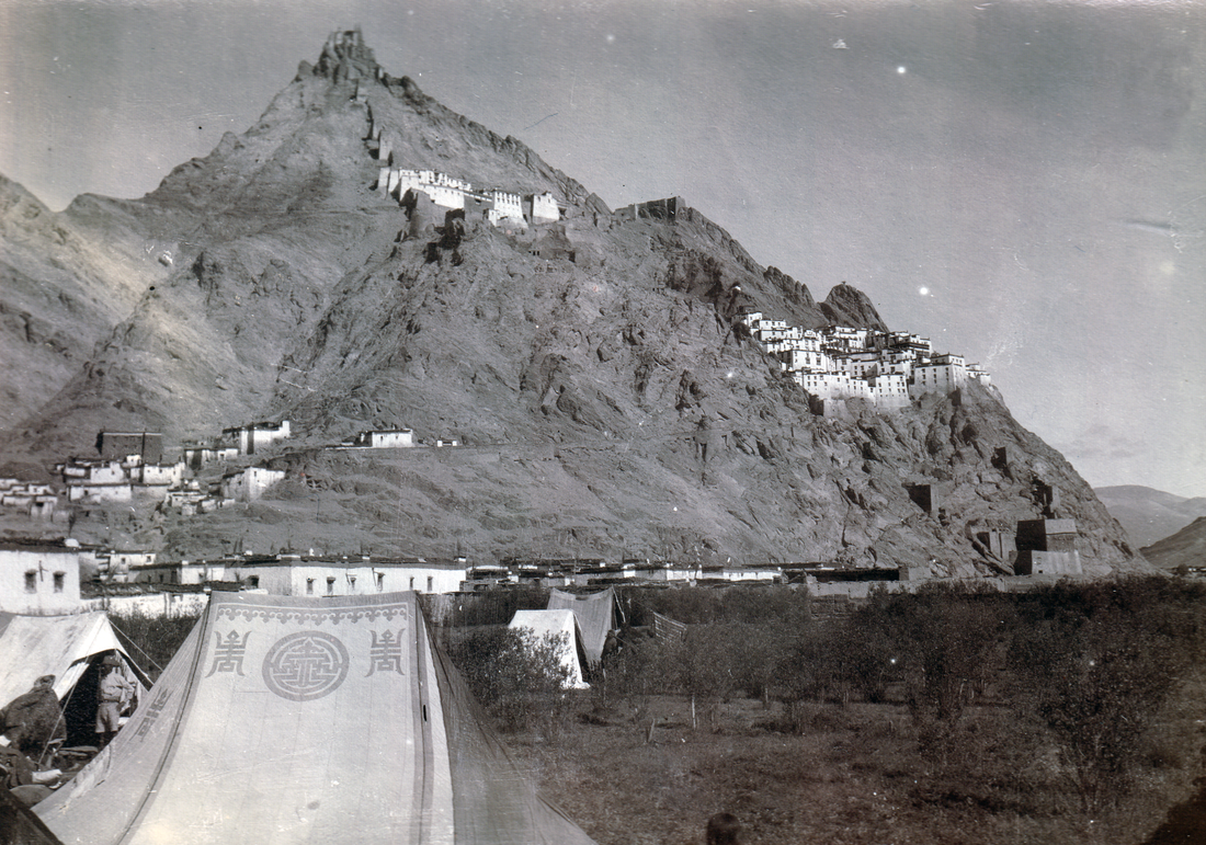

The monastery-fortress at Shekar. Howard-Bury described his team's arrival in the town: 'We then turned off Northwards up a side valley which led us to the town and fort of Shekar. This place was very finely situated on a big rocky and sharp-pointed mountain like an enlarged St. Michael's Mount. The actual town stands at the foot of the hill, but a large monastery, holding over 400 monks and consisting of innumerable buildings, is literally perched half-way up the cliff. The buildings are connected by walls and towers with the fort, which rises above them all. The fort again is connected by turreted walls with a curious Gothic-like structure on the summit of the hill where incense is offered up daily. On our arrival the whole town turned out and surrounded us with much curiosity, for we were the first Europeans that they had ever seen.' (Marian Keaney/Westmeath Library Services: Howard-Bury Collection)

Actor John McGlynn reads a segment of Charles Howard Bury's contribution to Mount Everest: the Reconnaissance.

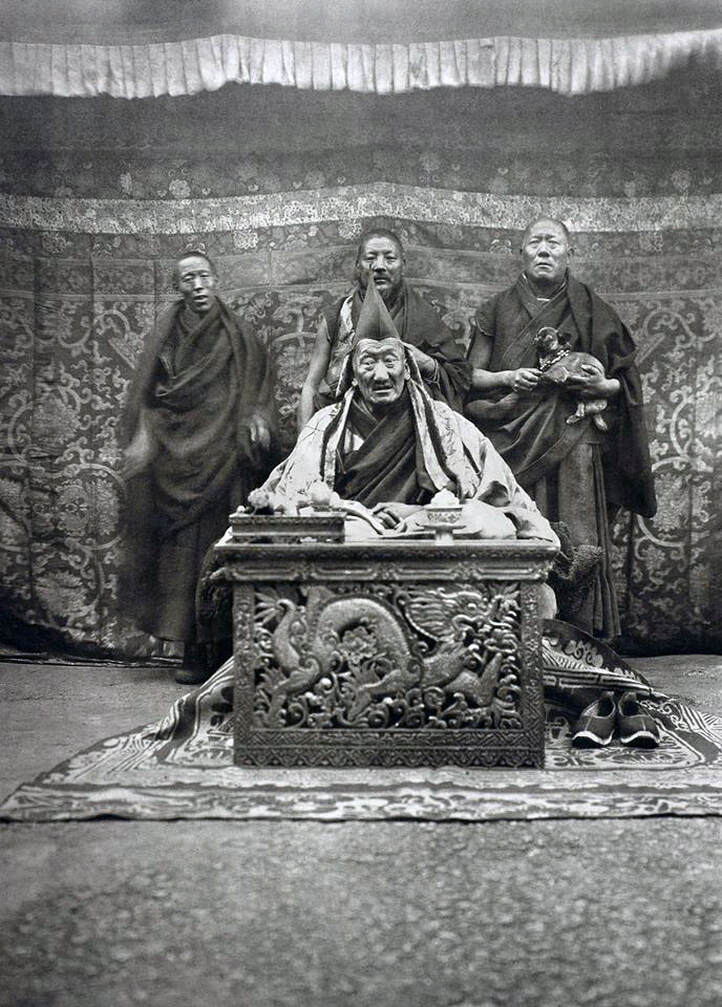

In the segment, Howard-Bury describes his visit to Shekar Chöte and the circumstances behind the photo below:

In the segment, Howard-Bury describes his visit to Shekar Chöte and the circumstances behind the photo below:

Howard Bury's photograph of the Abbot of Shekar Chöte became a sensation in Tibet: 'Before leaving we went in to see the Head Lama who had lived over sixty-six years in this monastery. He was looked upon as being extremely holy and as the re-incarnation of a former abbot, and they therefore practically worshipped him. There was only one tooth left in his mouth, but for all that he had a very pleasant smile. All around his room were silver-gilt Chortens inlaid with turquoises and precious stones and incense was being burnt everywhere. After much persuasion the other monks induced him to come outside and have his photograph taken, telling him that he was an old man, and that his time on earth was now short, and they would like to have a picture of him to remember him by. He was accordingly brought out, dressed up in robes of beautiful golden brocades, with priceless silk Chinese hangings arranged behind him while he sat on a raised dais with his dorje and his bell in front of him, placed upon a finely carved Chinese table. The fame of this photograph spread throughout the country and in places hundreds of miles away I was asked for photographs of the Old Abbot of Shekar Chö-te, nor could I give a more welcome present at any house than a photograph of the Old Abbot. Being looked upon as a saint, he was worshipped, and they would put these little photographs in shrines and burn incense in front of them.' (Photo taken from Mount Everest - the Reconnaissance, 1922).

'Lamas of Kharta Monastery' (Marian Keaney/Westmeath Library Services: Howard-Bury Collection)

The reconnaissance team established a base at Kharta, close to Everest in August 1921. It remained the base headquarters of the expedition until it returned to India in October, and all the expeditions that were made up the Kharta Valley, or into the Kama Valley, started there. Howard-Bury was impressed by the Kharta Valley and the sense of familiarity it engendered: 'As we descended into the valley again the glimpses of the lakes seen between the mists reminded me much of the upper lakes at Killarney. There were the same ferns, willows, birch and rhododendrons, and much the same moist atmosphere.' Howard-Bury had often visited Kerry during childhood holidays.

The reconnaissance team established a base at Kharta, close to Everest in August 1921. It remained the base headquarters of the expedition until it returned to India in October, and all the expeditions that were made up the Kharta Valley, or into the Kama Valley, started there. Howard-Bury was impressed by the Kharta Valley and the sense of familiarity it engendered: 'As we descended into the valley again the glimpses of the lakes seen between the mists reminded me much of the upper lakes at Killarney. There were the same ferns, willows, birch and rhododendrons, and much the same moist atmosphere.' Howard-Bury had often visited Kerry during childhood holidays.