Mother and Goddess

Although the mathematician Radhanath Sikdar established in 1852

that Mount Everest was the world's tallest mountain, it remained unmapped until

Charles-Howard Bury's reconnaissance team arrived in the region. Howard-Bury and his colleagues

would also explore the region's geology and encounter a wealth of local traditions regarding the mountain.

that Mount Everest was the world's tallest mountain, it remained unmapped until

Charles-Howard Bury's reconnaissance team arrived in the region. Howard-Bury and his colleagues

would also explore the region's geology and encounter a wealth of local traditions regarding the mountain.

Just before dark a very beautiful and lofty peak appeared to the Southwards. Our drivers called it Chomo Uri (The Goddess of the Turquoise Peak) and we had many discussions as to what mountain this was. In the morning, after taking its bearings carefully, we decided that this could be no other than Mount Everest.

We found out afterwards that the name, Chomo Uri, was purely a local name for the mountain.

Throughout Tibet it was known as Chomolungma — Goddess Mother of the Country — and this is its proper Tibetan name.

Charles Howard-Bury describes the expedition team's approach to Everest from Tibet. Excerpt taken from Mount Everest the Reconnaissance, 1921, by Charles Howard-Bury, George Leigh-Mallory and Alexander Wollaston.

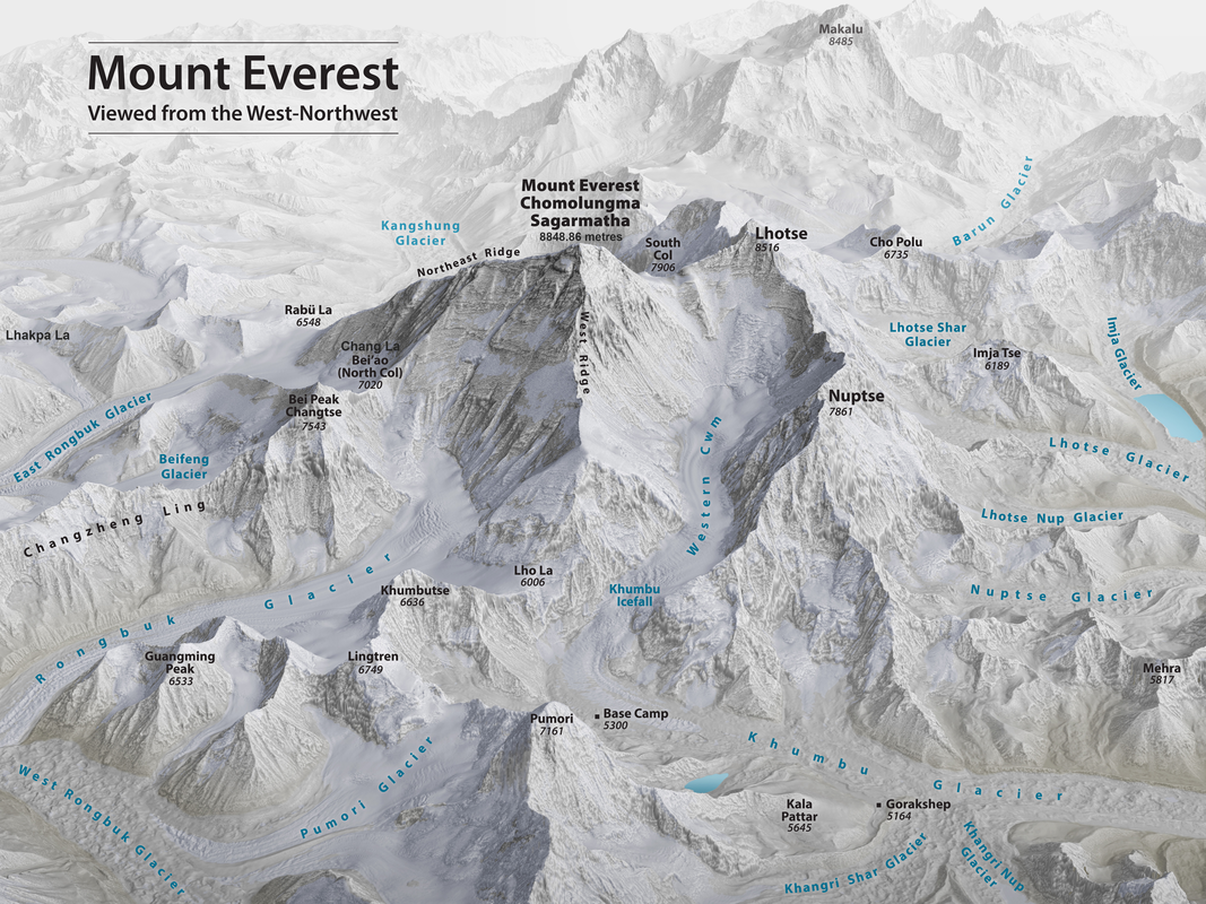

Everest, viewed from west-northwest. This map was created by Tom Patterson, a cartographer with the US National Parks Service, based on data from the US National Snow and Ice Data Center and the American Earth observation satellite, Landsat 8. In searching for a way to the summit, the 1921 reconnaissance team explored routes along the Rongbuk Glacier, the West Rongbuk/Pumori Glacier and along the Kharta Glacier, emerging at the head of the East Rongbuk Glacier (the Kharta Glacier is not shown on the map but is behind the area named Lhakpa La).

|

How to create the world's tallest mountains

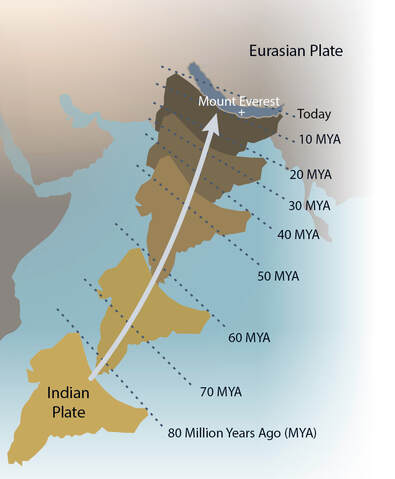

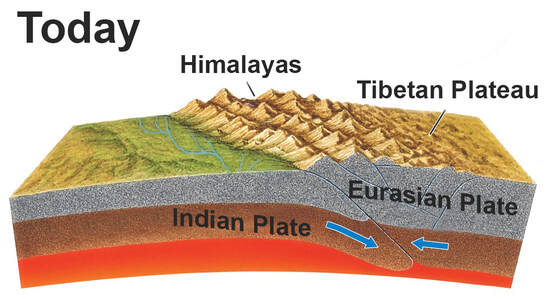

The origins of the Himalayas can be traced to around 200 million years ago, when the supercontinent of Pangea started to break apart, after which the Indian plate began to move northwards towards the Eurasian plate. As the continents converged and India pushed under Asia, the surface buckled and the crust thickened to form what would become the Himalayan mountain range.

The collision that formed the Himalayas is still continuing today. India pushes northward by about five centimetres each year but this movement is not always smooth. The continental plates can snag at different locations, causing pressure to build, which is relieved periodically by earthquakes along the many fault lines that cross the region. Those earthquakes, as shown by that which struck Nepal in April 2015, are often massive and immensely destructive. The 2015 earthquake, which measured 7.8 on the moment magnitude scale, caused multi-story buildings in Kathmandu to collapse and created landslides and avalanches across a wide stretch of the Himalayas, including Mount Everest. The tectonic activity beneath the Himalayas means that the mountains are being pushed ever upwards, rising by about a centimetre per year in some locations and by an estimated one millimetre per year at Mount Everest and its vicinity. In 2020, a combined effort by Nepalese and Chinese scientists concluded that Everest was then 8,848.86 metres (29,032 feet) high. As the mountains rise, they are constantly subjected to erosion by wind and water, which combine to scour away the surface, washing sediment into the myriad streams and rivers that descend to the lowlands. The wider Himalaya Hindu Kush ranges hold more glacier ice than anywhere else in the world besides the poles and they sustain 240 million people in their peaks and valleys. The mountain ranges also hold the headwaters of rivers like the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra that provide water to billions of people downstream. Mount Everest's position, 28° north of the equator, puts it at the edge of the Indian Monsoon which brings moisture and clouds from June to September. The coldest months are December and January and the best trekking is between these two seasons: March to May and October to November. Temperatures at the mountain's summit are never above freezing and during January temperatures can drop as low as -60° C. Aside from extremely low temperatures, hurricane-force winds and the accompanying wind chill are a grave danger to climbers. Those winds relax in the month of May and most climbers try to reach the peak during that short window. As we shall see during the exhibition, fierce winds would force the reconnaissance team from the North Col in September 1921. |

The trajectory of the Indian Plate over the last 80 million years.

It is still pushing towards the Eurasian Plate. India is moving towards the Eurasian Plate

at a velocity of about 5cm per year. |

The 2015 Nepal Earthquake caused immense damage in Kathmandu and across the country, leading to an estimated 9,000 deaths and 22,000 injuries.

The earthquake also caused landslides and avalanches across the region, including Mount Everest.

The earthquake also caused landslides and avalanches across the region, including Mount Everest.

|

The World's Highest Peak is...

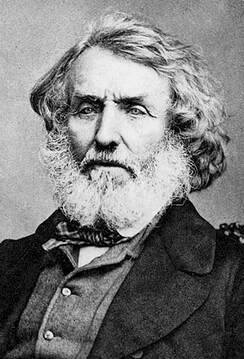

The Great Trigonometrical Survey was started by the East India Company in 1802 to survey the entire Indian subcontinent, a task that would take most of the 19th Century to complete. From 1823, the survey was managed by George Everest who retired in 1843, to be replaced by Andrew Scott Waugh. The survey teams reached the Himalayan region during the 1830s and by the end of the following decade they had come to suspect that a mountain, which they provisionally named ‘Peak B’ was, perhaps, the world’s highest.

Up to that point, Kangchenjunga – on the border of Nepal and the Indian province of Sikkim – was believed to be world’s tallest mountain. Foreigners were not allowed to enter Nepal, so observations were taken from within India. In 1852, Radhanath Sikdar, the survey’s 'Chief Computer', established beyond doubt that the peak, which they were then calling ‘Peak XV’, was indeed the highest mountain on Earth, with a mean height of 29,002 feet (8839.81 metres) obtained from measurements taken in six different survey stations. It was normal for the survey to use local names when naming peaks but Waugh claimed that he could not discover any local name for the mountain and that the prohibition on foreigners entering Nepal made it impossible for him to further investigate this topic. Waugh may not have been aware of Tibetan names for the mountain - one such name, Chomolungma, had been printed on maps in the 18th century - and he ignored Deodungha (or Devadhunga), the name by which the mountain was known in the area around Darjeeling. Sir George Everest objected to naming the peak in his honour. He had never seen the mountain, pointing out that his name (which he pronounced Eeev-rest rather then Ever-est) was difficult to pronounce in Hindi. Despite his objections, the title of Mount Everest was confirmed by the Royal Geographical Society in 1865 and this remains the most commonly used name to this day. As discussed later in the exhibition, Howard-Bury's team encountered names such as Chomo Uri, while in the vicinity of Everest. Apart from Everest, modern names for the mountain include Chomolungma (Tibetan), Sagarmatha (Nepalese) and Qomo-lungma Feng (Chinese). |

Radhanath Sikdar. He established that

Mount Everest is the world's tallest mountain. Sir George Everest objected to Mount Everest

being named in his honour. |

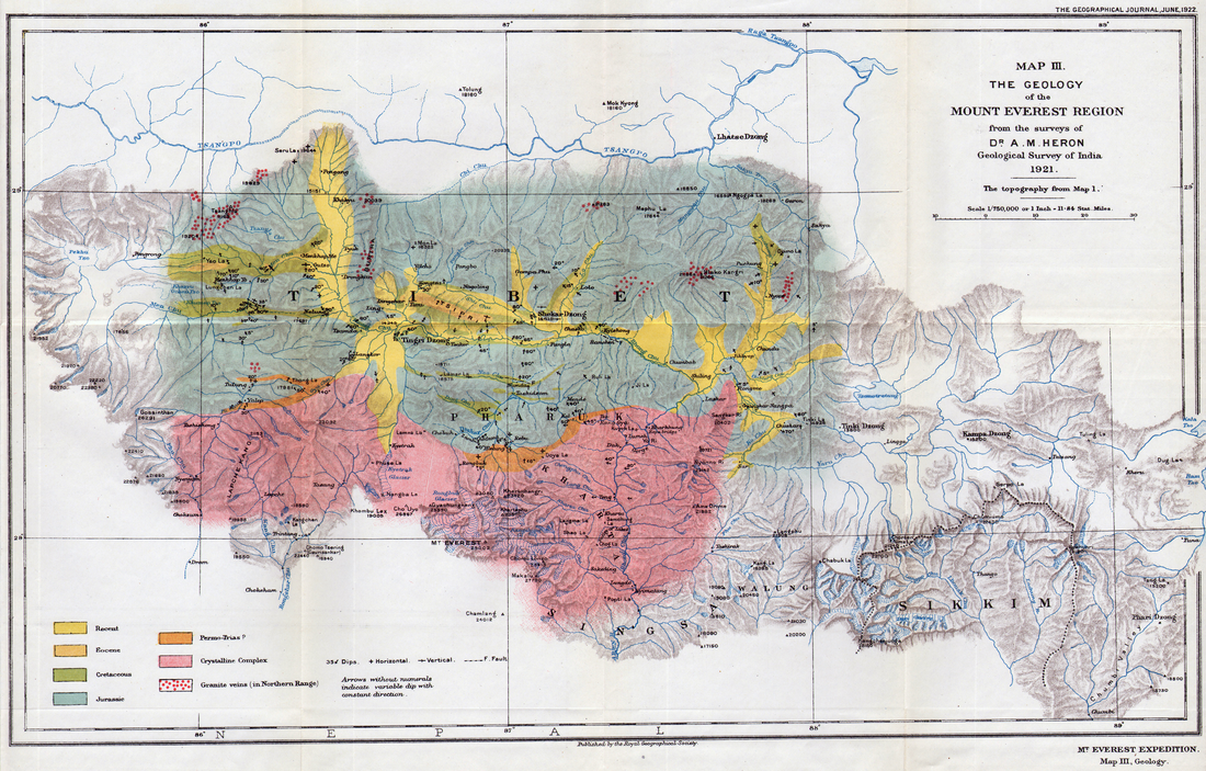

The map, showing the geology of the region around Mount Everest as it was understood in 1921, was produced by Scottish geologist Alexander Heron.

Heron was a member of the 1921 team and the map was published as part of the subsequent official account of the expedition.

Heron was a member of the 1921 team and the map was published as part of the subsequent official account of the expedition.

|

You can download the map

through this link | ||||||